There are stories of great authors in history writing 1,000-page manuscripts by hand. Today, that sounds like a needlessly laborious task; a book that might take a year to write by hand can now be typed in just a few months. But will the results be the same?

A saying keeps coming to mind as we continue to explore the science behind handwriting: there's no such thing as a biological free lunch. Just like dieting without exercise will leave you disappointed, switching from pen to keyboard for efficiency gains can have detrimental effects.

But why?

Kuniyoshi Sakai, a professor at the University of Tokyo and leader of his own research lab, Sakai Lab, has spent years investigating the human brain and language. Sakai and his team specialize in exploring how the neural pathways in our brains process input stimuli (speech, sounds, etc.) and the outcomes of constructing processes (writing, drawing, etc.). Most interesting to us, a company developing the smartest pen in the world, is their study on paper notebooks vs. mobile devices.

The Sakai Lab is one of the few research teams to compare digital devices to pen and paper, and the results are more impressive than we could have imagined. It appears that our brain's processing systems are more naturally harmonized with pen and paper compared to typing or writing on digital devices.

Kuniyoshi Sakai has been studying the brain for decades, initially starting with monkeys before switching to human subjects after the introduction of functional MRI techniques. This new technology, introduced in the '90s, allowed scientists to peer into brain functions like never before.

Sakai’s fascination with the human brain and linguistics blossomed while studying in Boston, where he met Noam Chomsky.

“[Chomsky’s] claim about the specialization or innateness in the brain has been really stimulating. His theories and hypotheses actually became the basis of my research.”

These experiences led Sakai to shift his focus from non-human primate brains to human brains.

But what are the differences?

“Most of our visual functions, for example, are based on primates. So, in that sense, our sensory and motor abilities are very similar to those of animals, like monkeys and chimpanzees. But when I moved from monkey studies to human studies, I realized that I should focus on how humans can think and create new things. We can naturally speak and write freely, but that’s the huge difference between humans and other animals.”

Unlike primates or other animals, who react to physical needs—hunting when hungry or nursing wounds when injured—human brains clearly have extra processes for comprehension and creation.

But how does this relate to handwriting?

It’s those specialized circuits that make the difference. It turns out that writing by hand better aligns with our brain's visual/memory/language systems than typing or writing with digital devices. Imagine handwriting with pen and paper as traveling via car or train; it’s slower, but you have more time to enjoy the scenery, while typing is like flying; it’s faster, but you’re landing at your destination without having to consider how you got there.

But science doesn’t work with analogies alone. So, Sakai went hunting for evidence in brain science. Where are these processes located in the brain? What are the input variables and outcome variations? How do these specialized functions work in the network?

“If you want to write something, you need to construct ideas and make sentences or phrases. Broca’s area is responsible not only for speech outputs (widely believed for more than 160 years), but for structural processing of sentences as we have shown that this particular region is critical for syntactic analyses while listening and reading.”

It’s this aspect of structuring that gives handwriting with pen and paper the upper hand. To confirm their findings, the lab set out to map the brain’s activity.

“We can actually measure the brain activity in each region as well as the degree of participants’ responses. So we can quantitatively attribute those activities to individual performances.”

After verifying the source of our language processing, the lab measured the comparative outcomes of analog writing (pen and paper) versus digital methods (smart pens or typing with tablets and smartphones). Unsurprisingly to those who use both methods, the analog methods significantly surpassed the digital ones.

The key difference lies in brain engagement and processing speed. Analog handwriting requires more from your structural processing system. The uneven strokes of a pen compared to typing on a keyboard engage more of your brain’s processing power with proper spatial information. That’s why even writing with a stylus on a tablet is noticeably less effective than handwriting with pen and paper.

“I think a softer pen like a fountain pen is more useful on paper because the tip is more flexible. When it’s softer, it allows for uneven strokes with rich information that enhance easier reading of letters and words.”

Let’s return to an analogy. Typing or writing with digital devices is like walking down a straight, even road. After a while, you won’t remember anything but the information around the road. In contrast, analog handwriting is more like walking through a woodland. You’re more engaged, paying attention to the scenery and the ground for potential obstacles. At the end of your walk, you're more likely to remember the woodland than the straight road.

“Writing on paper allows you to remember where you wrote something. After a few sentences, you can even recall where you wrote a specific word on the paper. It’s not just the sentences or words, but also the memory of the spatial positions and thoughts behind the words.”

You can experiment with this yourself. Have two friends take notes on a TV show, film, or article. Afterward, ask each what they thought of the media. Go a step further and ask where in their notes they wrote a specific comment or idea.

So what is happening in our brains to elicit this type of reaction?

“Many things happen simultaneously when you’re taking notes on paper. You need to select the key ideas instead of writing everything down. You have to understand the structure, comprehend the context, and create your own notes. This process engages your writing skills.”

This circular process is the secret behind handwriting. In comparison, typing—especially when taking notes—is closer to a one-way road. Your motor skills take over inputs to replicate them just in letters. It’s more like, "in through your eyes/ears and out through your fingertips."

“Typing is fast, but you may not think while you’re typing. Many students try to write everything down. That’s why they can’t choose the right concepts—they’re too busy to think.”

So, what are the outcomes of writing with pen and paper versus digital alternatives?

Writing by hand has immediate effects on your memory, comprehension, and creativity. This is because your brain processes the original inputs more thoroughly. These effects also extend beyond the moment of writing. If you incorporate handwriting into your routine, you’ll notice long-term benefits. Handwriting is a vital tool for a more productive and creative mind.

“Digital text is uniform, and it disappears quickly and completely when you close the application. Over time, your memory becomes less and less reliable. Use more natural methods instead!”

It’s well-known that scrolling through fast media has effects on your brain similar to fast food’s effects on your body. According to Sakai Lab’s research, the same can be said for relying on digital forms of writing and note-taking.

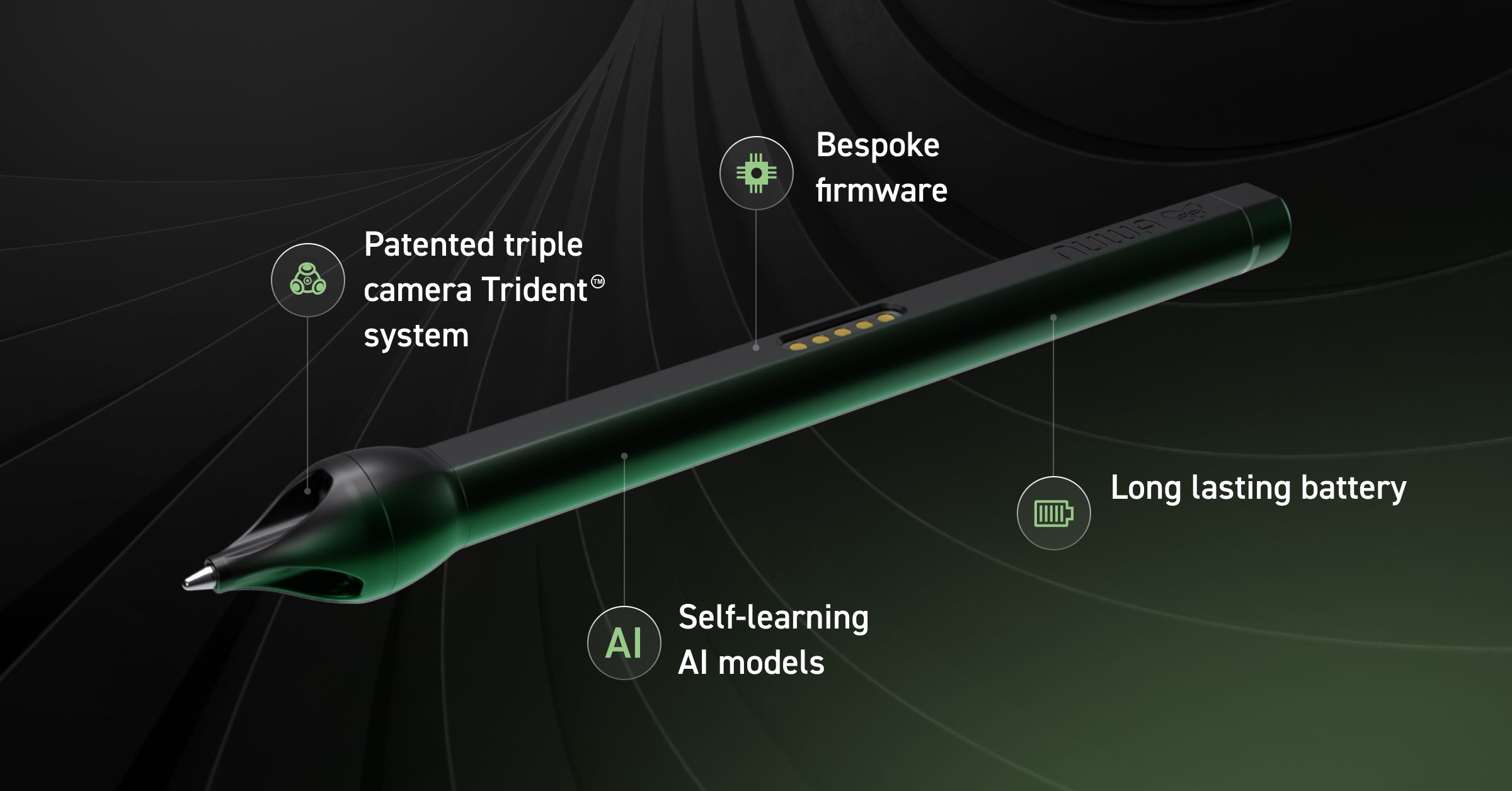

At Nuwa HQ, we’re working hard to create a smart pen that blends the best of both worlds. Thanks to research done by the Sakai Lab, we can confidently move forward. We hope that, given enough time, we’ll all return to the mental sanctuary of handwriting and reap the rewards of a slower pace of thought—without missing out on the interconnectivity the digital world offers.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.